Living Art: How “Kokuho” Chronicles the Making of a Master

The narrative begins in 1964 Nagasaki, where young Kikuo loses his yakuza father and finds refuge in Osaka as an apprentice to Hanjiro, a master kabuki performer played by Ken Watanabe. Lee—whose previous work includes “Hula Girls” and a Japanese remake of “Unforgiven”—structures the film around Kikuo’s relationship with Hanjiro’s son Shunsuke. While Shunsuke inherits his family’s theatrical lineage, Kikuo possesses something perhaps more valuable: an uncanny gift for onnagata, the demanding art of portraying female characters.

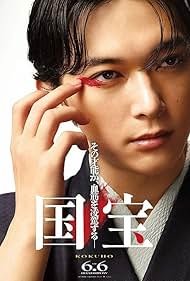

What distinguishes “Kokuho” from typical artistic struggle narratives is its refusal to clarify who Kikuo really is beneath the makeup. When Ryo Yoshizawa assumes the role from child actor Soya Kurokawa, he plays Kikuo with an intentional remoteness that contrasts sharply with Ryusei Yokohama’s warmer portrayal of Shunsuke. This ambiguity becomes the film’s central question: Has kabuki consumed Kikuo’s identity, or has he strategically hidden himself within its elaborate traditions?

Screenwriter Satoko Okudera’s adaptation of Shuichi Yoshida’s novel understands that kabuki’s hereditary nature creates its own drama. Without family credentials in the House of Tanban-ya, Kikuo must navigate a world where bloodline matters as much as talent. The film tracks these machinations across five decades, ending in 2014, though Lee keeps the focus tightly on the theater world rather than broader historical events—the atomic bomb’s aftermath receives only a brief mention, yet its shadow lingers.

The filmmaking itself mirrors kabuki’s aesthetic principles. Cinematographer Sofian El Fani employs extreme close-ups alongside expansive wide shots, capturing both intimate facial expressions and the full choreography of performance. The vivid color palette showcases Yohei Taneda’s production design and Kumiko Ogawa’s elaborate costumes with theatrical intensity. Particularly effective are the on-screen titles that introduce each kabuki play with its Japanese name, English translation, and plot summary—a choice that invites international audiences into stories of tragic love and honor without condescension.

Beneath its surface as a period piece, “Kokuho” quietly examines how ancient artforms survive in modern economies. The Mitsutomo Corporation’s sponsorship of the theatrical house represents the uncomfortable compromise between 17th-century tradition and 20th-century commerce. Yet kabuki endures in the film’s world much as it does in reality—not frozen in time but adapting while maintaining its essential character.

By the time Kikuo ages into middle years, Yoshizawa’s performance takes on an almost spectral quality. Among characters visibly weathered by their art’s physical demands, Kikuo seems oddly preserved, as though the roles he inhabits have protected him from ordinary aging while simultaneously preventing him from fully existing outside the theater. It’s a haunting metaphor for any artist who achieves mastery at the expense of a conventional life.

“Kokuho” suggests that becoming a national treasure requires a kind of self-erasure. Lee’s film respects its subject matter enough to spend substantial time showing actual performances, trusting audiences to understand why these characters sacrifice so much. The result is a rare artistic biography that actually conveys what makes the art worth pursuing—and worth the price.